The Drawing of St. Paul’s Cathedral

The silhouette of St Paul’s Cathedral is so important on the London skyline that it has a load of protected view corridors towards it from all around the city; if you’ve ever wondered why certain skyscrapers look like they’re leaning, it’s because they’re designed to avoid blocking one of those long views! But that’s just one of the latest reasons that makes St Paul’s one of the most important (and finest) buildings in the country - how could I resist drawing it?! Here’s a quick rundown behind-the-scenes of my process…

I - A good base

The first step for me is usually to gather some good reference images, stick them on a sheet, and start massing out the shape of the elevation itself. I prefer to draw orthographic views as they’re a bit more interesting - we see things in perspective normally, so flattening something out in 2D gives an alternate insight into how the building fits together. At this stage I’m using a big charcoal-type digital brush to block out the silhouette and get proportions feeling right, as well as making notes about key details to research next.

St Paul’s was designed by Sir Christopher Wren in 1668 after the original Cathedral was lost in the Great Fire of London. His original designs were criticised for being too dissimilar to traditional English churches, so Wren ended up creating a mash-up (technical term) that was based on the familiar Medieval English church plan but with significant influence from the continental Baroque classical styles of the time. This is most apparent in the famous dome, which calls back to St Peter’s Basilica in Rome, and rises to 111m (365ft) to define one of the most important parts of London’s skyline.

II - First details

Once I’ve got the building broadly massed out, I’ll start sketching over in a thinner line weight for the next level of detail. This is where I really start digging into the reference materials, trying to break down the shapes into actual architectural elements! In this instance, I’m looking closely at subdivisions in the elevation, paying particular attention to proportions and spacing of horizontal and vertical elements.

The Dome is an incredibly complex piece of design and engineering, being ‘double-skinned’ like that at St Peter’s Basilica. However, Wren made the cavity between interior and exterior faces much greater to allow for a huge structural brick cone through the middle, which is then reinforced with massive wrought iron chains!

III - A full sketch

By the time I’ve sketched out the whole building in the previous stage, I’ll have generally set the dimensions for the drawing itself. I used the floor levels of the various public galleries to set the vertical dimensions, with widths taken from a basic measured drawing I found on the internet. This stage is then the final ‘sketch’ layer before the main drawing, so I’ll spend a lot of time reviewing references and checking proportions / detailing.

The West Front of St Paul’s is an exceptional example of a Classical portico that stretches the full width of the aisles. The portico makes great use of paired columns that are narrower on the upper storey, creating a visual hierarchy (which is reinforced by the use of Corinthian capitals on the lower and Composite capitals on the upper), and balances vertical and horizontal emphasis too. The towers allow the styling to transition from the grand portico and columns on the West Front to the more planar character of the south and north walls, rendered as ashlar masonry with paired pilasters.

IV - Inking begins

Now that I’ve got the full base sketch completed, I can start inking over the top. This is the most meditative part of the process, and I often find myself almost getting into a trance when drawing things up at this stage! I often scribble out a few different versions of some of the trickier details to make sure that they look right at the scale I’m drawing in; things like the capitals, reliefs and statues are all quite fiddly and the trick is to make them look convincing without fussing too much!

There are 17 statues at St. Paul’s Cathedral, depicting a variety of apostles and evangelists. The statues on the West Front were carved by Francis Bird around 1718, including St Paul himself standing centrally over the pediment. The statute of Queen Anne, which sits in front (and not shown in my drawing) was also carved by Bird. Bird’s original statue was actually replaced in 1886, as it had been damaged by repeated attacks throughout the 18th century!

V - More detail

The ‘outline’ ink is now done, so next up is working into the detail with a much finer lineweight. Even though these are completely digital brushes, I still refer to them as ‘S Pen’ and ‘One Eight’, as that’s what they were called when I was under apprenticeship! As I love the analogue aesthetic I try to keep to traditional architectural drafting lineweights as much as possible, even when I’m fully digital.

And speaking of weights, Just the dome on its own weighs 65,000 tons, and is actually based on a catenary profile rather than a true hemispherical dome. I learned that the hard way constructing the geometry for my drawing, and wondering why it was feeling squashed drawn as a hemisphere!

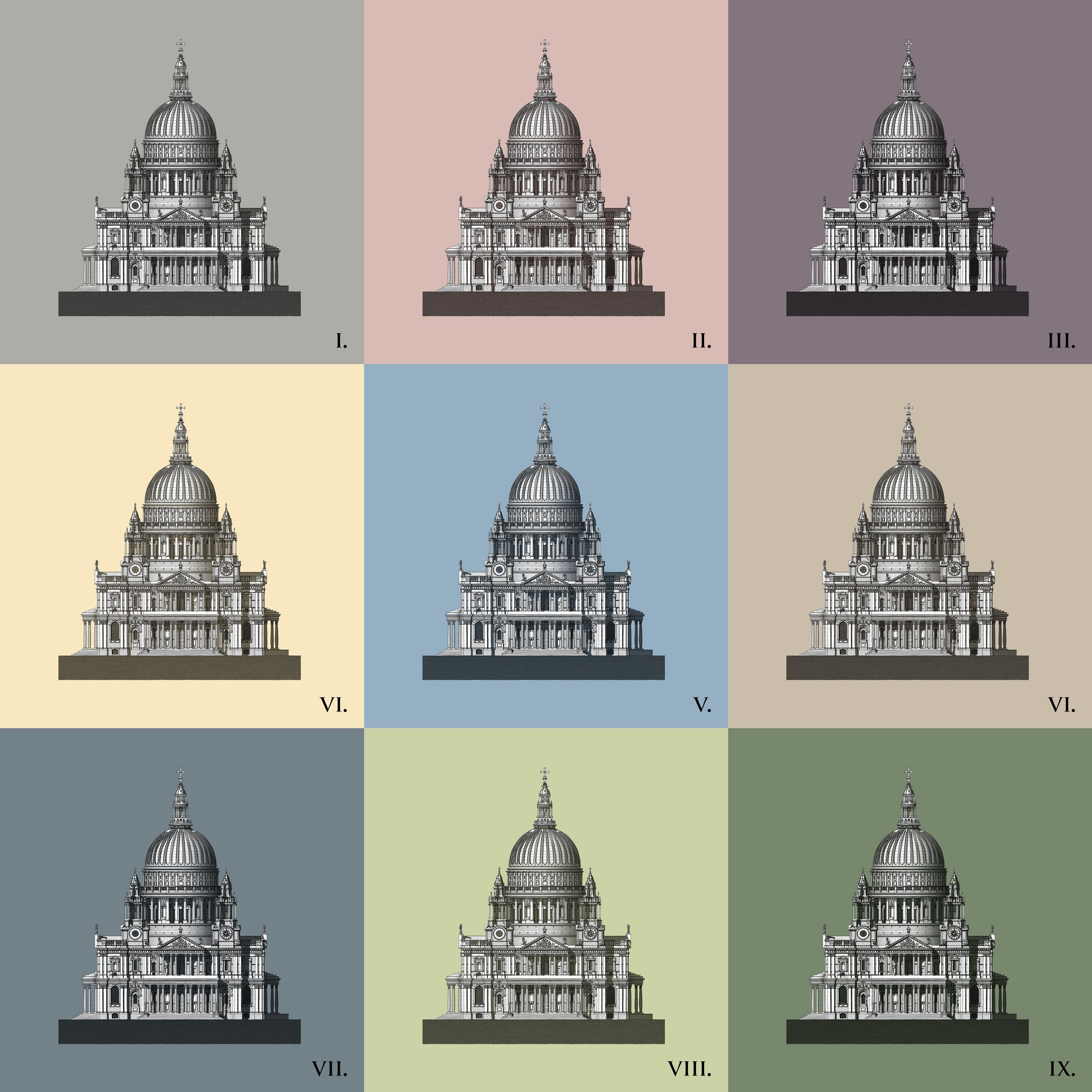

VI - Thumbnails

Where a building has some really interesting and unique details I like to spend a bit of time doing thumbnail sketches to get to know it all a bit better... in this instance, the statues are absolutely fantastic! I’ve picked a couple of the key ones from the west front to share here; first up is St Paul, bearing an ENORMOUS sword. St Peter appears next... but he’s stuck with a rooster, which feels a little like he’s been short-changed! St James is on the end, wielding a pilgrim’s staff, which is better than a rooster but still not as good as massive bloody sword.

The statues are enormous - each one is about twice human size! St Paul himself is almost 4 metres tall, which is about the same as 57 real-life roosters! The carved rooster that appears with St Peter is about 1.5m tall which, terrifyingly, makes it taller than an average 10 year old child.

VII - Final lines and shading

Now that I’ve finished up the super thin linework to indicate materials, detailing and depth, it’s on to the shading stage - this is where things really start to pop! Getting shadows right can be really tricky, and its usually a balance of cleverly calculated geometry… and then just having a guess and hoping for the best! I might do an in-depth tutorial on how I work out shadows on orthographic drawings, so let me know in the comments if you’d be interested in that. In this instance, I start with the deepest shadows and work out to the lighter ‘gradient’ shadows. All this work is done in grayscale, as I’ll be adding some colour glazes over the top for the last stage…

Sir Christopher Wren was the first person to be interred at the Cathedral, in 1723. The words “Lector, si monumentum requires, circumspice” are engraved above his tomb, which translates to “Reader, if you seek his monument, look around”. As far as humble-brags go, that one is up there!

VIII - Printing prep

With background and colour glazing in the shadows now finished, the last step is to prepare the drawing as a limited edition print. This just really means sticking some nice titles on it, checking it sits right on a page, and then sending off for some proofs. It’s super important to make sure that the final prints will match the fidelity of linework I’ve spent ages drawing in, and that the colours I’ve picked are going to reproduce accurately… especially if someone is going to have it hanging on their wall! Once I’m happy with the final quality of everything, it’s over my specialist print lab to run off the limited editions, and get them listed for sale.